Dec 11, 2025 · 8 min read

The failure of my life

When I was 18, I believed the story everyone tells you: work hard, get good grades, get into a top school, land a stable job. That’s financial security.

So I did exactly that. I enrolled in a CPGE—France’s brutal two-year prep program for elite engineering schools. I studied constantly. I barely slept. I passed the exams.

And I failed.

Not completely—I got into a good school. Just not the best school.

It turned out to be the luckiest failure of my life.

Here’s what happens when you don’t get into the top school: you can’t rely solely on prestige. Nobody’s going to hand you anything because of a name on your diploma. You have to build things.

So at ENSEEIHT, I joined the Junior-Entreprise and became Vice-President. I built companies. I learned to invest my money. I spent my nights reading books.

And as I was reading, I started to get an answer to a question I always strugged to answer: why do some people get rich while others stay poor?

The conventional answer is effort. Work harder. But I’d just spent two years working harder than I ever had, and I’d failed at the thing I was working toward. Meanwhile, I watched people who seemed to work less end up in better positions. Something didn’t add up.

With everything I’d been reading, I finally had the tools to answer it. Five years after that failure, I’ve arrived at a conclusion that would have shocked my old self.

And I figured out.

Poverty isn’t about how hard you work. It’s about where you sit in the network.

What I mean by “the network”

This sounds abstract. Let me make it concrete.

Think about the internet. A handful of websites—Google, Facebook, Amazon—capture almost all the traffic. Millions of other sites exist, but they’re invisible. Nobody visits them.

Economy works the same way. A few nodes capture most of the money. Everyone else fights for scraps.

Indeed, this is exactly what Albert Barabási studied. Complex networks like the internet, social networks, biological systems all follow the same pattern.

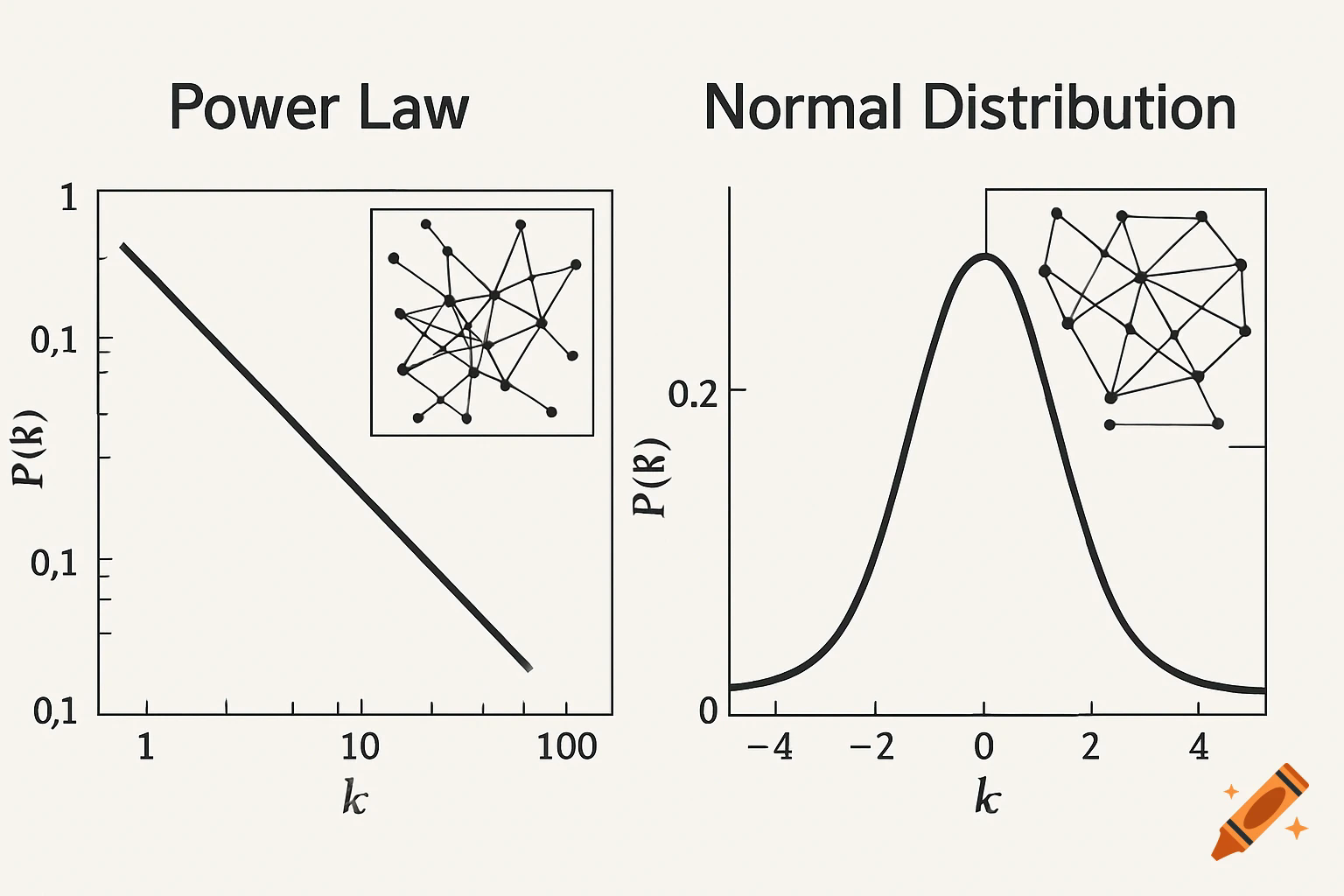

Most things we learn about in school follow a normal distribution. Test scores, remember you something right?. The classic bell curve.

But wealth doesn’t work that way. Wealth follows a power law. A tiny number of people have almost everything. Everyone else has almost nothing.

When I first learned about this, my reaction was: that’s unfair.

But then I thought about it more.

It’s not about fairness

Here’s where I lost most of my friends in debates. Because my conclusion wasn’t “we should fight the system.” My conclusion was “we should understand the system.”

Barabási’s work showed that networks naturally grow in a way that favors hubs. This is called the “rich-get-richer” effect. The more connections a node has, the more likely it is to get new connections.

Once I understood this, I started seeing it everywhere:

- The popular kids in school attracted more friends.

- Rich people had more opportunities to get richer.

- Successful companies attracted more customers.

None of this is a conspiracy. It’s just how networks work. If you’re mad about it, you’re mad at math.

So instead of wasting energy fighting the system, I decided to play with it.

Preferential attachment

Here’s the key insight: in any network, new nodes prefer to connect to nodes that already have lots of connections.

This is called preferential attachment. And it’s why early advantages compound.

Think about it practically. If you’re a new graduate looking for a job, would you rather have a recommendation from:

- Someone nobody knows

- A well-connected person everyone respects

Obviously the second. And that person got well-connected by having connections in the first place. The rich get richer.

This created a new question when I understood it:

How do you become a hub when you’re starting from the edge?

The paycheck trap

Here’s where most people go wrong. They try to solve the problem by working harder at their job.

If you work h hours at w dollars per hour, your income is:

Linear. You work more, you get a little more. That’s fine if you want a comfortable life. There’s nothing wrong with that.

But it won’t make you rich. It can’t, mathematically.

Hubs don’t sell time. They capture flows.

Imagine you create something—a platform, a product, a piece of content—that attracts k users, each generating value v. Your income becomes:

And here’s the magic: k can grow exponentially because of network effects.

Even a small growth rate compounds into something huge over time. That’s why founders, investors, and creators can get so rich while employees with similar talent stay middle-class.

I’m not saying quit your job. I’m saying understand the game you’re playing.

Why most people don’t do this

If building something that captures flows is so obviously better than trading time for money, why doesn’t everyone do it?

I used to think it was because people didn’t know. But that’s not it. Most people intuitively understand that starting a business or creating something could be more lucrative than their job.

The real reason is courage. Or rather, the lack of it.

Adler was right about this. He said courage is the foundation of a happy life. Most people know what they should do. They just can’t bring themselves to do it.

Being rich requires sacrifice and risk. You might lose everything. That’s terrifying. And for most people, the stability of a paycheck is worth more than the potential upside of building something.

That’s a perfectly rational choice. I’m not judging it.

But you should make it consciously, with full understanding of the tradeoffs.

The math of hubs

Let me get a bit more technical, because I think it helps to see the math.

Barabási discovered that most real-world networks are “scale-free.” This means:

- Preferential attachment: new nodes connect to nodes that already have many connections.

- Hubs dominate: a few nodes end up with most of the connections.

- Power-law distribution: the probability that a node has k connections follows:

Where γ is typically between 2 and 3.

In plain words: in any network, a tiny number of hubs capture most of the connections. Most nodes are peripheral.

Think about companies. BlackRock, Vanguard, Palantir—these are hubs. They don’t just have money. They have connections. They sit at the center of flows.

A concrete example

Let’s make this tangible.

Say you have 2 connections, each worth $100/year to you. Your income: $200/year.

A hub has 1,000 connections, each also worth $100/year. Hub income: $100,000/year.

Now imagine you work twice as hard and double your connections to 4. Your income: $400/year.

Still nothing compared to the hub.

This is why small differences in connections early on create massive differences later. It’s not luck. It’s math.

Why I changed my mind about social safety

Let’s step ahead a little bit. Before, I used to be skeptical of welfare programs. I thought they created dependency.

Then I understood networks better.

Here’s the thing: if peripheral nodes collapse—if people lose housing, jobs, food—the network itself gets weaker. Demand drops. Markets shrink. Eventually, even the hubs feel it.

Social programs aren’t charity. They’re stabilization mechanisms. They keep the edges of the network alive long enough for some of those nodes to climb toward the center.

France has plenty of problems with its welfare system. But the basic idea is sound. You need to keep people in the game.

The path from edge to center

So how do you actually move from the periphery toward being a hub?

The math tells us: you need to increase your degree—your number of meaningful connections.

Here’s how I think about it:

Step 1: Stabilize your base. You can’t take risks if you’re worried about food and shelter. Get the basics sorted first.

Step 2: Build assets. Skills, projects, side hustles. Anything that gives you capabilities beyond your job.

Step 3: Increase connections. Not just more connections—valuable ones. People who can open doors, teach you things, collaborate with you.

Step 4: Solve problems at scale. This is where preferential attachment kicks in. If you can solve a problem for many people, you attract more connections, which lets you solve bigger problems.

Eventually, the value you capture scales superlinearly with your connections:

That’s why hubs get exponentially richer. It’s not greed.

One more thing

I also wanted to talk about Bitcoin. Not because of its price or the technology, but because of what it represents.

The current financial system has central banks as the ultimate hubs. They control the flows of money. Bitcoin is an experiment in creating a network without those centralized hubs.

Whether it succeeds or not, I think it’s asking the right question: can we design networks that are more fair to peripheral nodes?

I don’t know the answer. But I find the question interesting.

What I’ve learned

Poverty isn’t about effort. It’s a structural position in a network.

Hubs capture most of the flows. Small nodes survive linearly.

But here’s what gives me hope: networks are dynamic. You can grow your connections, increase the value of each link, and climb toward hub status.

The question isn’t how to work harder. It’s how to change where you sit.

Start thinking less about hours worked and more about:

- Where you sit in the network

- Who you’re connected to

- What flows you’re capturing

That shift in perspective changed everything for me. Maybe it will for you too.